China Global Newsletter | Edition 2 – December 2020

China commits to go carbon neutral by 2060 – Implications for overseas investment

In September this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping surprised many by announcing to the United Nations General Assembly that China aims to achieve peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and will go carbon neutral before 2060. China had previously indicated it would reach peak emissions “around” 2030, but the carbon neutrality pledge is new.

In order to achieve these goals, China will have to undergo radical shifts at home, where fossil fuels play a huge role in the energy and power industries that are central to the country’s economy. Although the commitment only applies to domestic emissions, the announcement also raises important questions about China’s contributions to global carbon emissions through overseas investment and finance.

In this edition of our Global China Newsletter, we take a look at the implications of this announcement and what it means for overseas investment.

Topics covered include:

- China’s carbon neutral by 2060 announcement

- China’s domestic carbon emissions

- China’s overseas carbon footprint

- Country profile: China’s role in Cambodia’s high-carbon energy shift

- Industry profile: Chinas role in powering Indonesian nickel for the electric vehicle industry

- Climate change policy developments in China

- Recent investment trends

- Steps towards a greener future

- A path forward: Rhetoric to action

China’s Carbon Neutral by 2060 Announcement

In the short time that has passed since his September speech to the United Nations where President Xi announced China’s intention to go carbon neutral by 2060, he has reiterated this commitment in various high-level events. This includes the 12th BRICS Summit in November and at the G20 Riyadh Summit, where he stated: “China will honor its commitment and see the implementation through.”

According to a study published by Tsinghua University’s Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development, in order to hit the 2060 goal, China must reach net zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, with emissions of all greenhouse gases down 90% on 2020 levels.

The influential team behind the Tsinghua report proposed a roadmap including replacing almost all coal power with renewables, cutting industrial emissions, and increasing use of carbon capture and storage technology, along with utilizing offsets. The government is yet to publish its own detailed roadmap.

>> back to top

China’s domestic carbon emissions

The shift required to achieve peak emissions by 2030 and neutrality by 2060 will require concerted effort at all levels of government and industry. For over 15 years China has been the world’s top aggregate emitter of CO2. Currently, China accounts for 28% of global CO2, almost double the second largest emitter, the USA.

China’s manufacturing, construction and industrial processing sectors alone contribute more to global greenhouse gas emission than the European Union’s entire output in all sectors combined. The sectors in China’s economy which account for the greatest emissions include coal power generation, iron and steel production, and industrial processes like cement.

Even under the increased centralization of authority during the Xi Jinping era, it is still challenging to ensure central mandates are implemented at the subnational level. Industries such as steel and cement are dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), many controlled at the provincial and local level. These SOEs and those who regulate them have financial, political and local economic development incentives to continue high emission operations.

Nonetheless, China has made significant strides in reducing pollution in the past 10 years, and although there is still much work to do, China’s “green economy” has played an important role in this shift. Through a combination of large investments into renewable energy, upgrading of existing technology for higher efficiency, and other multi-faceted carbon reduction campaigns, China’s carbon output has plateaued since 2013.

Recent COVID fiscal stimulus provided additional funding for renewable energy development such as wind and solar and electric vehicle and lithium battery production – industries in which China is already a global leader. Other innovations like the much talked-about national emission trading system could create incentives for the gradual reduction of emissions needed to meet the 2060 goal.

But despite these developments, the scale of the challenge cannot be underestimated. According to Global Energy Monitor, China had over one million megawatts (MW) of operational coal capacity as of July 2020. Although around 100,000 MW has been retired, a similar amount is now under construction, and an additional 150,000 MW are in the planning stages.

If projects continue to come online at a faster rate than they are being retired, the 2060 goal will prove unobtainable. According to the Tsinghua study, in order to hit the 2060 pledge, China will have to increase the percentage of power generated by non-fossil fuels from around 40% to 90% in the next 30 years. For this to be achievable, existing plants may need to be retired early, and construction of new plants phased out.

>> back to top

China Power Podcast

China’s Commitments to Fighting Climate Change featuring David Sandalow from the Center on Global Energy Policy, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University.

The Belt & Road Podcast

China’s Global Power Database: China’s global power plant investments data at your fingertips! featuring Ma Xinyue & Cecilia Han Springer from Boston University’s Global China Initiative.

China’s overseas carbon footprint

If China does go carbon neutral by 2060, it could lower global warming projections by 0.2 to 0.3 degrees Celsius – the largest reduction since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015. However, taking action at home will not be enough to address the global challenge of climate change: Chinese companies and banks continue to play a major role in the expansion of overseas fossil fuel and other carbon intensive projects. While the commitment to reduce emissions at home is welcome, there are concerns that this could result in further export of excess capacity in dirty energy and carbon intensive industries.

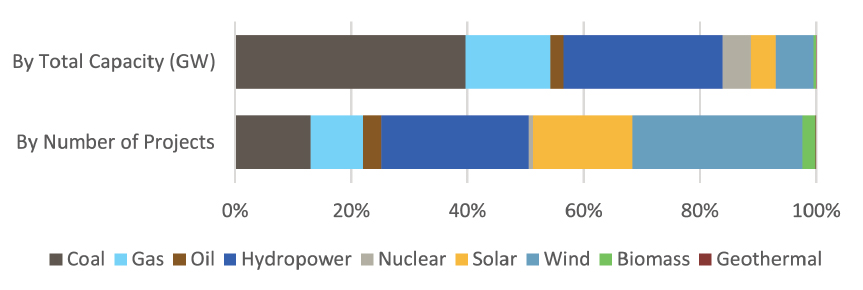

Data published by Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center in its China’s Global Power Database, documents Chinese policy banks and firms being involved in 777 power plant investments in 83 countries between 2000 and 2018. Forty percent of these plants are coal-powered, with combined capacity of over 74 gigawatts (GW). Almost three quarters of these projects were funded by China’s policy banks, with 40% located in Southeast Asia and 31% in South Asia. The center estimates that those currently operating contribute an estimated 314 million tonnes of CO2emissions per year, with plants under construction likely to contribute a further 211 million tonnes when they come online.

Distribution of Energy Sources of Overseas Power Plants with Chinese Investment and Finance, Understanding China’s Global Power by Xinyue Ma

In addition to anxiety around increasing carbon emissions, there are also serious concerns that as the world shifts towards renewable energy sources, many global coal plants will become stranded assets. With the cost of renewable energy dropping, battery storage capacity increasing, and policy incentives for renewable energy becoming more common, existing coal plants will become less and less competitive and eventually unprofitable. Indeed, as discussed in more detail below, there is a shift taking place in Chinese overseas energy investment, with renewable energy investments on the rise. However, Chinese renewable energy companies face challenges expanding overseas. Overseas wind and solar projects tend to be much smaller than fossil fuel projects, and are so far less likely to receive Chinese state-backed financing.

According to the Global Power Database, between 2000 and 2018, only 4.4% of policy bank lending went to solar and wind projects. A recent paper by Bo Kong and Kevin Gallagher found that Chinese overseas renewable investment was held back by both “pull” and “push” factors. On one hand, many countries do not actively seek Chinese financing for renewable expansion. At the same time, policy banks often view overseas renewables as unattractive as the banks have less experience financing such projects and they are often small scale and distributed, rather than grid-based. In the words of one bank official, they are “pocket change”, and banks prefer large, grid-connected energy projects valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

If China does follow through on the commitment made in September, it sets an important example, and puts it in a strong position to support energy transitions in countries where Chinese finance and firms are active. In many cases, countries that are hosting Chinese energy projects do not have carbon-neutrality commitments and coal power is seen as an accessible and proven source of energy required to fuel economic growth. China can in part address this with policies and incentives that encourage its own banks and companies to more vigorously pursue overseas renewable investments, and assume the role of a global climate change leader, rather than an exporter of emissions.

>> back to top

Country profile: China’s role in Cambodia’s high-carbon energy shift

One country in which China has a disproportionate footprint in terms of energy development is Cambodia. As of 2018 almost 75% of Cambodia’s power supply came from power plants built and at least partially financed by Chinese companies and banks. All but one of Cambodia’s operational and under construction coal plants have involvement of Chinese companies. The majority of finance for Cambodian energy projects comes from China Eximbank, China Development Bank, Bank of China and ICBC.

In response to severe drought-induced power shortages of 2019, the Cambodian government has prioritized expansion of coal capacity. Construction has commenced on one 700 MW project in Sihanoukville, and approval of another 700 MW plant in Koh Kong province and a 265MW plant in Oddar Meanchey was fast-tracked.

Community consultation on these projects has been minimal, beyond negotiations around compensation for those directly affected by land acquisition, and there is a dearth of information on exact project locations, what technology will be used, and how impacts will be mitigated. It is unclear whether environmental and social impact assessments have been conducted, but no such assessments have not been made public, and civil society groups have not been consulted.

Without published impact assessments, the public can only speculate on the impacts these projects will have, but other coal plants in Cambodia have been associated with severe coal dust pollution that impacts severely on surrounding villages. Most of Cambodia’s coal plants are coastal, and impacts on fisheries have never been publicly studied and quantified.

At present Cambodia generates 50% of its energy via hydropower dams, but ongoing expansion of coal and plans for developing gas could shift the energy mix drastically to almost 75% fossil fuel. As a result, Cambodia may face the withdrawal of major international brands who produce in or purchase products from Cambodia, and do not want to be associated with fossil fuel powered manufacturing.

A growing number of global brands have signed on to the RE100 initiative. This includes several major clothing brands who produce or source from Cambodia. Under RE100, companies commit to working towards producing and/or sourcing from factories that are 100% powered by renewables, or when this is not possible, to offset the difference. The more coal present in the Cambodian energy mix, the more expensive those offsets will be, which could push companies to relocate to Vietnam or elsewhere. Five major global brands – H&M, Adidas, Puma, Gap and Specialized – articulated these concerns to the Cambodian government in a private letter obtained by regional media.

H&M, the Swedish clothes company, has been especially vocal, making its position known to the Cambodian government and in public that if grid energy does not become cleaner “industry will find more attractive countries that are able to offer such energy opportunities.” If other brands follow suit, the economic impacts for Cambodia could be huge: the garment sector is the backbone of the economy, employing at least 800,000 people, the majority of which are women.

This communication from the private sector has led to a subtle shift in government messaging on renewable energy, but so far no change to short term fossil-heavy energy plans. If the current coal expansion does result in the loss of factory jobs, it will undermine the years of development assistance and investment that has flowed from China to support the expansion of Cambodia’s export-oriented manufacturing industry.

>> back to top

Industry profile: China’s role in powering Indonesian nickel for the electric vehicle market

China’s leadership has pushed for years to become a world leader in electric vehicle battery technology and production. In order to achieve this goal, China is supporting firms to access important ‘new materials’ that are domestically scarce, including battery-grade nickel.

Indonesia is home to the world’s largest nickel reserves. President Joko is using the country’s outsized share of global supply as a basis for an industrial policy encouraging foreign investment in high-end nickel processing, stainless steel production, electric vehicle component and battery manufacturing facilities. Chinese firms are key players in this development.

The $8bn Morowali Industrial Park in Central Sulawesi Province is one of the main locations for stainless steel and battery development in Indonesia. Since 2013, firms within the park have used the regions’ deep nickel reserves to become global leaders in stainless steel production. But the industrial park has also brought harmful environmental and social impacts to local communities. The zone’s development rapidly expanded open-pit mining in the region, resulting in the loss of forest resources, an increase in the intensity and frequency of flooding, and heavy pollution in the rivers used by downstream communities for farming.

Local communities have also been affected by the zone’s dedicated 2,000MW coal-fired power plant. The plant has caused spikes in acute respiratory infections in local children and has forced thousands of families who rely on fishing to go further offshore due to contaminated runoff and wastewater. Multiple Chinese banks including China Development Bank, China Export-Import Bank and ICBC have provided over $2bn in financing for these coal plants. There are currently plans to further expand the plants’ capacity to 2,900MW in the near future.

A common process used to make battery-grade nickel is called High-Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL). Different consortiums composed mainly of large private and regional state-owned Chinese firms have begun development of five, billion-dollar HPAL facilities throughout Indonesia, two of which are located within the Morowali Industrial Park.

The process used to make battery-grade nickel is extremely energy intensive and, under current plans, the nickel produced in the Morowali Industrial Park by the HPAL facilities will be powered by the China-financed coal power plants. While there are no publicly available estimates of the amount of energy that will be needed to power these facilities, it is possible that the energy production could negate a sizeable portion of the gains made by the use of the nickel in electronic vehicles charged with 100% renewable energy.

>> back to top

Climate change policy developments in China

China’s policy and economic trajectories are guided by its Five-Year Plans, and the 14th Five-Year Plan for 2021-2025 is now being developed. Following President Xi’s September announcement, all eyes will be on the plan and the extent to which it sets out a road map for reaching carbon neutrality by 2060.

Following the release of the Five-Year Plan in March 2021, topic-specific plans will also be published. China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment is developing a Five-Year Plan for environmental protection, and has informed media that this will include specific measures for hitting peak carbon emissions by 2030.

In October, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment along with four other institutions, including the banking regulator, issued the Guiding Opinions on Promoting Investment and Financing to Address Climate Change (关于促进应对气候变化投融资的指导意见). Although not legally binding, the guidelines further articulate the state’s push for both policy and commercial banks to implement the climate change related decisions of the Party and State Council. The guidance includes calls for banks and regulators to support “low-carbon construction” of the Belt and Road, fulfill social responsibilities and address climate risks.

>> back to top

Recent investment trends

The COVID-19 pandemic inevitably impacted China’s outbound investment during the first half of the year (see China Global Newsletter Edition 1). Data to the end of October shows total overseas investment is still down slightly on the same period in 2019, dropping by 3.2% to $86.38 billion. However, during the same period, investment in the original 64 Belt and Road countries was up 23.1% at over $14 billion. The value of new contracts has begun to climb again, but is still down 4.4% on last year.

State-owned enterprises – major drivers of global energy investments – have seen their fortunes improve, following some difficult months during the height of the pandemic. According to China’s SOE regulator, in the third quarter of 2020, SOEs actually saw improved performance on the same period last year, with revenues and profits up. While the overall picture may be improving, several major SOEs are in trouble. In one high-profile case, the Henan provincial SOE Yongcheng Coal and Electricity Holding defaulted on a $151 million bond, which Caixin described as the “tip of its debt iceberg”. Many coal companies are now facing hard times with profit in the coal sector dropping over 30% this year.

>> back to top

Steps towards a greener future

Although confronting the challenge of climate change and addressing the climate impact of Chinese overseas investment is a major task, there are some hopeful signs.

November saw a major win for communities and civil society groups that have for years called for the Kenyan government and investors to drop the 1,050 MW Lamu coal plant. It is feared that the proposed plant will cause irreparable environmental, social and cultural damage to Lamu, home of Lamu Old Town, a UNESCO Heritage site. In November, local civil society coalition Save Lamu made public that ICBC had communicated to them that it was no longer financially involved in the project, after earlier reports indicated it was considering providing a $1.2 billion loan. A representative from China’s embassy in Kenya later added that there are no Chinese firms currently involved in the Lamu project. With ICBC dropping out, the project will likely struggle to find financing. This followed a decision in June by Kenya’s National Environmental Tribunal to cancel the project’s environmental license.

In recent months there has been a spate of deals signed for major overseas renewable projects financed and/or developed by Chinese banks and companies. PowerChina signed a contract to develop a $1 billion, 800 MW wind farm in Ukraine. In Vietnam, Tianfu Energy signed a deal for two wind farms totalling 560 MW, and Gezhouba for a 350 MW offshore windfarm. Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, Myanmar announced in October the results of a bidding process for construction of 30 solar power projects totalling over one GW. Six Chinese firms won the tender for 16 of the projects.

Although not a Chinese bank per se, the multilateral Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank was initiated by China, is based in Beijing, and led by a former Chinese finance ministry official. For the past few years, civil society groups and some bank shareholders have pushed for the bank to explicitly exclude coal from its portfolio, but the bank’s board has ultimately rejected this call. However, the president has publicly stated that the bank will not finance coal, which he reiterated in September, extending the commitment to any projects “functionally related to coal”.

Another important development came in the bank’s first Corporate Strategy, adopted in September, which set a target of reaching or surpassing a 50% share of climate finance in its financing approvals by 2025. While the president’s public statement and the new climate finance target were welcomed, civil society groups continue to push for an explicit policy commitment on coal exclusion, but there continues to be resistance from some shareholders. This leaves the bank a step behind its multilateral peers, many of which have excluded coal from their portfolios and enshrined this in policy.

>> back to top

A path forward: Rhetoric to action

Shifting to lower carbon development models both inside China and overseas will require significant policy shifts at the state level, and banks and companies active overseas will need to drastically rethink their investment priorities.

More broadly, it is important that whatever projects Chinese companies and banks are involved in follow best practices, and fit the standard of “high quality” articulated by policy makers in Beijing. For example, replacing coal projects with destructive large-scale hydropower projects will not support the “green recovery” that many are calling for in the post-COVID world. Along with a shift to climate friendly energy, Chinese investors and regulators need to enhance compliance with international social and environmental standards across the board.

Phasing out coal and other fossil fuels will impact workers in industries and places where coal mining and other carbon intensive activities dominate local economies. Additional efforts will be required to ensure these people are not left behind, and social programs and re-training will be essential as new growth models are explored and developed.

An increasing number of stakeholders are taking steps to phase out coal. Siemens Energy announced in November that it will no longer take on new business to supply coal-fired powered stations. In September, US energy giant General Electric announced that it intends to exit the new-build coal power market. Japanese and Korean banks have been major financiers of coal projects across Asia, and numerous banks have now signaled a commitment to move away from coal project, including state-backed banks Korean Development Bank and JBIC, and commercial lenders KEPCO, Shinhan, KB financial, JERA and Mitsui. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, announced in December that the UK will end direct government support for the fossil fuel energy sector overseas.

The Philippines announced in October that it would place a moratorium on approval of new coal plants. In December, the Filipino commercial bank RCBC committed to end financing of coal projects. These developments come in the context of massive public opposition against coal expansion and a ground-breaking climate complaint against the International Finance Corporation over its indirect investments in fossil fuels by more than 120 citizen groups and communities in the Philippines, supported by Inclusive Development International and Recourse. In August, Bangladesh announced plans to review 29 planned coal plants and consider the possibility of converting them to natural gas. This was largely motivated by concerns around lack of financing, rather than environmental issues, but indicates the decreasing availability of finance for these polluting projects.

With a growing number of countries formalizing their commitments to achieving peak carbon emissions and banks and corporations gradually adopting policies to phase out coal, pressure will increase on China to do the same. Importantly this means both adopting and implementing the policies necessary to ensure that it achieves its domestic climate commitments and ensuring Chinese companies do not simply export emissions through overseas investments. Without concerted efforts to address this now, China risks being left behind and will miss the opportunity to be a global climate leader.

In his September speech, President Xi stated that the Paris Agreement “outlines the minimum steps to be taken to protect the Earth, our shared homeland, and all countries must take decisive steps to honor this agreement”. All eyes will now be on China to see if it is ready to match rhetoric with action.

>> back to top

Further reading

Thomas Hale, Chuyu Liu & Johannes Urpelainen (2000), Belt and Road Decision-Making in China and Recipient Countries: How and to What Extent Does Sustainability Matter? ISEP, BSG, and ClimateWorks Foundation.

Lee Jones & Shahar Hameiri (2020), Research Paper: Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy’ How Recipient Countries Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Chatham House.

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletters here.

If you haven’t already, you can also subscribe below to receive an email alert when our next newsletter is published.

This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of Oxfam Hong Kong.

(The contents do not necessarily reflect the position of Oxfam Hong Kong.)