China Global Newsletter | Edition 3: March 2021

Taking Stock of the Belt and Road Initiative

2020 was a difficult year, with the Covid-19 pandemic taking a huge toll on countries across the globe. Although China was one of the first countries to bring the epidemic under control, global investment projects implemented by Chinese companies and financed by Chinese banks likely suffered, especially where the projects concerned were integrated into global supply chains that suffered through the pandemic.

This came at a time when China’s overseas investment was already falling. 2020 marked the fourth consecutive year of decline. There has been some speculation that this decline marks the end of China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). More likely, we are seeing a readjustment of the BRI, which from the outset has been a flexible framework drawing together numerous aspects of China’s global economic and diplomatic relations.

This edition of the China Global Newsletter begins by looking at the unfolding crisis in Myanmar since the military coup of February 2020 and how it may impact Chinese interests in the country, then goes on to take stock of where the BRI stands now, and what direction we may see it turn in the near future.

Topics covered include:

Crisis in Myanmar: China’s Response and Implications for the BRI

On the morning of 1 February 2021, the world awoke to news of a coup in Myanmar, with the military deposing the democratically elected National League for Democracy (NLD) and announcing a one-year state of emergency. This followed the military-aligned opposition claiming fraud in the November 2020 election, in which they were resoundingly defeated by the NLD. Figures in the NLD leadership were subsequently arrested and charged with a range of offences, including possessing 10 walkie-talkies without having appropriate paperwork and violating Covid-19 restrictions. Over 100 have been killed by security forces since, with many more injured or detained and held incommunicado.

To date, China’s response to the coup has been muted. The day after the military takeover, state news agency Xinhua published an article titled “Major cabinet reshuffle announced in Myanmar”. Subsequently, the Chinese ambassador to Myanmar gave interviews in which he urged all parties to avoid violence, stating the “basic rights of the people” must be protected, and that the situation was “absolutely not what China wants to see”. This muted response is in line with China’s long-standing principle of “non-interference”, and stands in contrast to the strongly worded statements that have come from the United States, European Union, Singapore, UN officials, and the G7, among others.

Following the 2015 election through which the NLD first came to power, China realigned its bilateral relationship, after decades of support for the military government. The NLD expressed early on that it was prepared to work with China, and Aung San Su Kyi travelled to Beijing in 2017 to attend the Belt and Road Forum and expressed support for the initiative. A crucial part of the BRI is the China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), which comprises a series of planned infrastructure projects linking China to the Indian Ocean via Myanmar.

Negotiations on specific projects progressed slowly, but in early 2020 during a state visit by Xi Jinping, 33 memorandums of understanding and other agreements were signed. This advanced the controversial and long-stalled Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone, as well as the Kanpiketi Business Park in bordering Kachin and the New Yangon City project. In January 2021, a MoU was signed for the feasibility study of a railway connecting Mandalay with Kyaukphyu, another important project under the BRI and CMEC umbrella. This occurred just prior to a visit from foreign minister Wang Yi, where Aung San Suu Kyi expressed support for CMEC and committed to coordinate with China on its development. The coup occurred less than three weeks later.

A number of companies have spoken out about the current situation, with one statement coordinated by the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business signed on by 24 international companies and almost 80 local enterprises calling for a “swift resolution”. Twelve members of ACT on Living Wages, including major international brands, signed on to a statement expressing concerns, stating: “Responsible business requires a context where fundamental human rights are respected.” The CEO of Singapore’s SembCorp, which built and runs Myanmar’s first internationally tendered power plant and has plans for a major industrial zone has said the coup has thrown planned projects into doubt. Several companies, including Japan’s Kirin – which was under pressure from human rights groups for its military links even before the coup – have announced that they will sever ties with military owned entities, and major clothing brand H&M announced it has suspended placing new orders with factories in Myanmar. So far, no Chinese companies have joined these initiatives or made similar public statements.

So where does this leave Chinese projects – planned, under construction, and in operation – in Myanmar? Although China gained extensive experience dealing with the military prior to the democratic transition in 2015 and maintained cordial military ties since then, the fallout from the coup will inevitably impact Chinese commercial interests. Already protests have spread to Chinese-invested projects, including the Letpadaung copper mine, a joint venture involving Chinese state-owned NORINCO and Myanmar military-owned MEHL, where 2,000 striking workers joined the growing civil disobedience movement. Media reports on leaked official documents also indicate that China is extremely concerned about the security of the Myanmar-China Oil and Gas Pipeline.

At present the public outcry against the coup shows no sign of relenting, but if the military does crush the protests, and Chinese projects continue to move forward, they will likely encounter increasingly unfavourable public sentiment from a citizenry that overwhelmingly opposes the actions of the military. International companies operating in or sourcing from Myanmar are watching closely to see how the situation unfolds. If the military does hold on to power, many are likely to leave, and global buyers will seek alternative markets. This directly threatens the potential success of the BRI in Myanmar, which seeks to support infrastructure development not only to facilitate access to the Indian Ocean and to transport resources to China, but to support the development of Myanmar’s nascent industrial sector, which will stagnate without access to global markets and international investors.

>> back to top

The Decline and Refocusing of Chinese Overseas Finance and Investment

Chinese Overseas Investment and Finance Drops

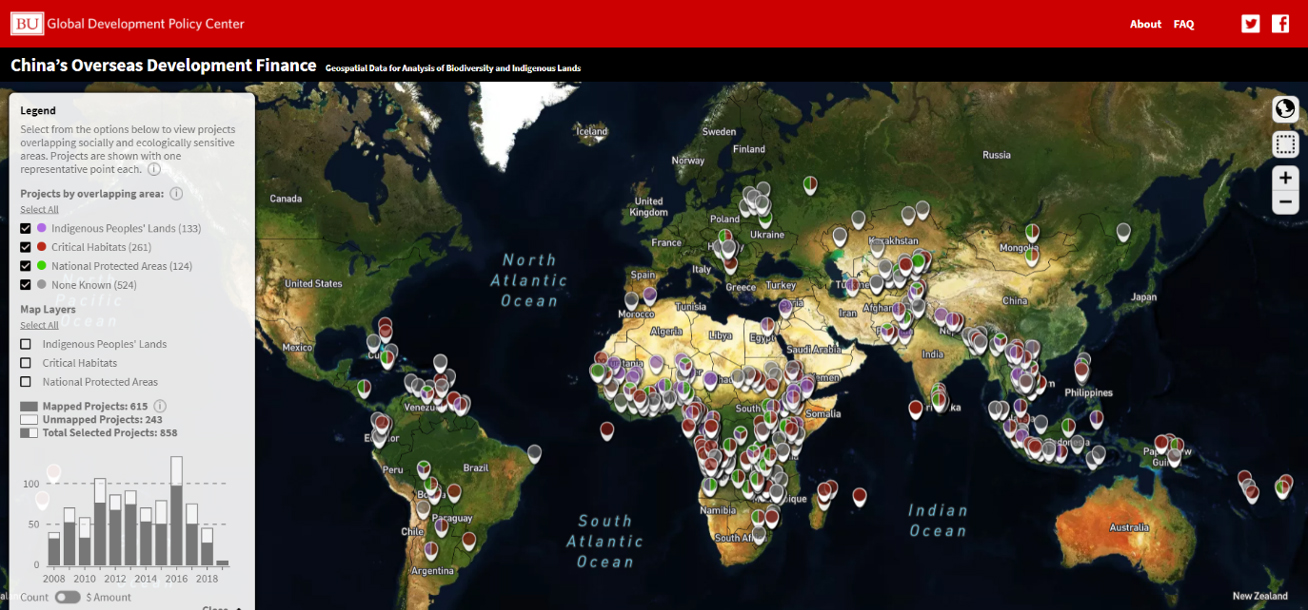

Both Chinese investment and Chinese financing have dropped significantly in recent years. In 2020, a number of datasets were published showing a dramatic decline in the volume of outbound finance from China. One that attracted considerable attention was the China’s Overseas Development Finance Database from the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University. The database tracks overseas loans from China’s policy banks, the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank). It tracked loans for 858 projects worth $462 billion between 2008 and 2019.

The data shows that after peaking at $75 billion in 2016, overseas finance from these two banks dropped precipitously to just $4 billion in 2019 – a decline of 94% in three years. Although much media coverage in the past few years has presented the BRI as catalysing a new wave of Chinese global finance, this decline actually began in 2016 – just one year after the Belt and Road was first formally articulated in writing by China’s National Development and Reform Commission.

It is important to note, however, there are some financial flows not covered by this data. Crucially, it does not cover policy bank investments in funds and financial intermediaries. Nor does it include finance from China’s state-backed commercial banks, such as ICBC and Bank of China, which are playing an increasingly important role in development projects across the globe. In middle-income countries especially, commercial banks may be as important or even more important than policy banks. However, other institutional datasets track this information, and although they adopt different methodologies, all show a similar decline following the peak of 2016.

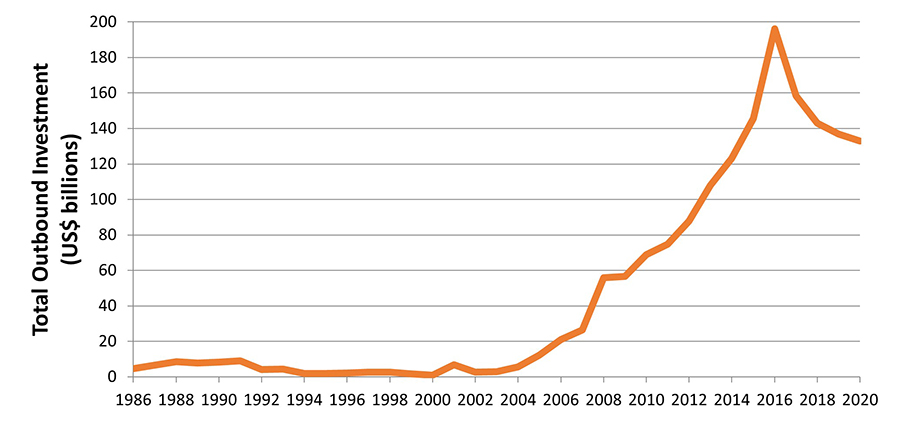

Official data on outbound investment from China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) also reflects the post-2016 trend.

There are various reasons for this slowdown. Geopolitical tensions between China and the U.S. and Australia have had an impact on investment in the past few years. Tightening of regulations on capital outflows from China dampened property investment and high value mergers and acquisitions. High profile missteps by Chinese investors in countries such as Venezuela and Pakistan also exposed the myriad risks major infrastructure projects encounter in fragile political environments. In several countries, new governments have come into power and pushed back on the terms of expensive infrastructure projects, leading to renegotiations. The pandemic has brought to the fore the debt risks that many countries have been juggling for years. All of this is likely to have factored into financing and investment decisions in recent years, and will continue to do so going forward.

The various datasets can help us assess the trajectory of China’s global finance, but focusing on the headlines may obscure more localized trends. One major development that has received less attention is that while global investment is down, investment in Belt and Road countries has increased. While MOFCOM data shows a 39% drop in total global investment between 2016 and 2020, investment in Belt and Road countries remained steady during this period, and saw an 18% year-on-year increase in 2020. (Note: this covers the initial 64 countries officially recognised by China as 沿线国家, or “along the Belt and Road”).

This drop in overseas investment and finance potentially represents a rebalancing and refocusing of investment and development priorities. The slowdown may create breathing space both for civil society groups working with communities impacted by high-risk projects, and for progressive policy makers in China seeking to strengthen regulatory frameworks governing overseas projects.

Revisiting the Belt and Road Concept

While it is possible the decline in China’s overseas investment will continue, reports of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) running aground are premature and miss the totality and flexibility of the BRI’s framework. As evidenced in recent high level documents, such as the White Paper on China’s International Development Cooperation discussed below, and the BRI’s addition to the constitution of the Communist Party of China in a 2017 amendment, the BRI is here to stay even if it’s implementation is going through a process of readjustment.

Dominant media narratives on the BRI tend to focus on China’s role in major infrastructure projects, but these projects are just part of the picture. With this in mind, it is useful to revisit the original vision for the BRI, which is often overlooked in commentary that focuses solely on the infrastructure component. The BRI was first explained in writing in 2015. This set out five main pillars:

Policy coordination – Facilities connectivity – Unimpeded trade

– Financial integration – People-to-people ties

While facilities connectivity has received most attention, the other four pillars are equally important to the initiative. Policy coordination can be seen in the establishment of platforms such as the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), which brings together China and the five downstream Mekong countries. Trade is a major focus of the BRI, and ties directly to infrastructure projects that create the physical connectivity that make trade and industrialization possible. The BRI is frequently referred to in bilateral trade discussions, and even has a dedicated chapter in the Cambodia-China Free Trade Agreement signed in late 2020.

In terms of financial integration, China led the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and jointly launched the New Development Bank with the other BRICS countries. China also funded the establishment of the Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance (MCDF), which brings together eight international multilateral development banks, with the vision of increasing high-quality infrastructure investments in developing countries in compliance with international standards. China also continues to develop the “people-to-people” aspect of the BRI via cultural and academic exchanges, tourism cooperation, providing scholarships, and conducting training in areas such as journalism.

Viewing the BRI as a holistic wide-ranging global vision, rather than a meticulously crafted program of infrastructure projects, is a more helpful basis for understanding its intent and significance. As a broad vision for China’s connection to and integration with other countries and global systems of finance, investment and trade, it makes sense for the BRI to evolve, as it appears to be doing now, in response to changing global economic conditions.

Global China Navigates the Pandemic

Chinese state agencies involved in the BRI have been eager to promote the progress made under the BRI despite the challenges of 2020, with one think tank under the National Development and Reform Commission stressing the initiative’s “impressive resilience, vitality and appeal amid the pandemic”.

Covid-19, and the diplomacy that emerged around provision of personal protective equipment, vaccines and other supplies, was accompanied by the rhetoric of a “Health Silk Road”, further evidence of the adaptive nature of the BRI. Meanwhile, new countries signed on to the BRI in 2020, including the Democratic Republic of Congo and Botswana, and in November, China signed a major multilateral trade deal, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnershiptreaty (RCEP), with 14 Asia-Pacific partners.

Inevitably, Chinese overseas projects were hit by the pandemic (see China Global Newsletter #1). A recent report by Overseas Development Institute found 15 major overseas projects worth at least $2.4 billion ran into problems during 2020 for various reasons, including the pandemic. It can be assumed that many smaller projects encountering challenges went unreported as border closures, labour shortages and market conditions took their toll.

As one example, in Cambodia, the exponential growth of the real estate sector has been driven by Chinese developers and Chinese property buyers. The pandemic exacerbated an already cooling property market, and has resulted in hundreds of projects halting mid-construction often leaving local and Chinese workers unpaid. Investors that were able to complete or keep projects on track now face a growing oversupply problem, with tens of thousands of condos on the market and not enough buyers. Those who did buy units with the hope of renting them cannot find tenants, leading to fears of the property bubble bursting, which could have a significant impact on Cambodia’s economy.

While some overseas infrastructure projects hit roadblocks, many continued to progress. This includes highway and transmission projects in Pakistan and sections of the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway in Indonesia. China-Europe freight train traffic also increased by 50% in 2020.

New deals were signed in 2020, including a construction contract for 2×600 MW coal plant in Turkey to be developed by Energy China International, and the landmark Laos-China railway is on schedule to be complete by the end of the year. Some controversial projects have managed to weather the storm, including the socially and environmentally risky Dairi Prima Mineral mine, developed by a subsidiary of state-owned China Nonferrous Metal Mining, which has raised serious safety concerns among local communities.

Some struggling projects benefited from economic stimulus provided by China’s policy banks. In early 2020, China Development Bank and the Ministry of Commerce issued a notice calling for such projects to apply for additional financial support. Eximbank also provided bailout funds to impacted companies, releasing almost $12 billion in 2020, with a focus on sectors related to foreign trade and manufacturing. A group of 265 global civil society groups wrote to MOFCOM, CDB and Eximbank in 2020 calling for such stimulus to avoid high risk overseas projects, but no information has been released on which projects and companies received bailout funds.

>> back to top

Recommended Podcasts

China-Africa Project

Why China’s Cutting Back on Overseas Lending featuring Yan Wang from the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University.

The Belt & Road Podcast

Easy Money is Rarely Easy: Jessica Liao on Infrastructure Financing and Export Credit Agencies, North Carolina State University

Chinese Overseas Investment and the BRI in a Post-Covid World

While it may be premature to be talking about a “post-Covid” world with many countries still dealing with the impacts of the pandemic and its economic fallout, some countries have brought things under control faster than others, and as vaccines roll out, there is hope that a return to something closer to normality is within reach.

As countries get back on track, many will be taking stock of planned projects and reassessing their economic viability. Looking forward, both China and countries hosting Chinese-backed investments will likely have a heightened awareness of risks that come with major development projects—principally economic, but also environmental, social and political risks. Financial risks will likely be central to China’s assessments of future projects, especially in countries emerging from the pandemic with heavy debt repayment burdens. One example of a project that has struggled to move forward since first envisioned several years ago is the Inga 3 hydroelectric dam in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

High Risk: The Inga 3 Dam

Since 2017 China Three Gorges and its 25% partner, Spain’s AEE Power Holdings, has held the rights to build and operate the planned 11,050MW Inga 3 dam. The project’s estimated $14 billion price tag is nearly 40% more than the DRC government’s entire 2020 budget. The project would also require additional investments in associated mining, industry and trans-boundary transmission lines to create sufficient energy demand for Three Gorges to make a return on investment. In 2020, President Tshisekedi reportedly sought to accelerate Inga’s development by reducing its scope to a 4,800MW project but reports suggested that Three Gorges saw the reduced scope as a non-starter because the reduced energy supply created too much financial risk for the company to move forward with the project.

Since then the project has gained interest from German Government officials and manufacturing firms and the Australian mining company Fortescue. Three Gorges appears to remain the lead developer as of March 2021, but no Chinese policy bank or state-owned commercial banks have agreed to finance the project. With the DRC’s economy suffering a severe shock in 2020, piling on more debt at this stage could be disastrous. Moreover, civil society groups have opposed plans to develop Inga 3 because of concerns around forced resettlement and extensive environmental impacts, with the dam threatening to flood the biodiverse ecosystem of the Bundi valley, an area populated and used by local populations for agriculture, fishing, hunting and gathering for generations. Groups have also raised concerns about the inadequate impact assessment process and failures to comply with local law.

Moving Forward on the Carbon Neutrality Pledge

Following China’s commitment to go carbon neutral by 2060, as discussed in the second edition of the China Global Newsletter, increased attention is falling upon China’s global energy investment. Although Chinese companies still play a major role in this sector, data from the Global Development Policy Centre indicates that financing for energy projects from the China Development Bank and the Eximbank is at its lowest since 2008. However, Chinese commercial banks are increasingly active in this space, and Chinese companies have continued to announce new engineering, construction and procurement contracts for energy projects, including coal plants in Cambodia, Indonesia, and Turkey, during the pandemic period.

The change in the US administration could create revitalized space for discussions around collective actions for addressing climate change, and all eyes will be on the UN Climate Change Conference COP in late 2021 to see how this plays out. Against this backdrop, several Chinese policy documents have been issued in recent months relating to climate finance (returned to below).

In addition, major Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have begun to announce plans to address their carbon emissions in line with the 2060 commitment, including major fossil fuel companies such as PetroChina, China National Offshore Oil Corporation and State Power Investment Corporation. Detailed plans have not yet been released, but SOEs are connected to much of China’s energy and high-emissions industries, both at home and globally, and concerted decarbonization efforts from these actors will be essential in the coming years.

Rhetoric from China continues to emphasize “sustainable” and “high quality” overseas projects, and in his address to the World Economic Forum in Davos, President Xi Jinping stated that China will continue to promote sustainable development and “advance high-quality Belt and Road cooperation”.

Deepening Integration into Global Supply Chains: Bauxite in West Africa

While media attention on Chinese overseas projects is often framed as a quest for resources, there is less focus on the more complex story of how Chinese projects, especially those focused on extractives and commodities, fit into broader global supply chains. Investment in the African bauxite sector is a useful example. Guinea sits on the world’s largest untapped bauxite reserves, and Chinese companies have established or are developing a number of large mines and associated infrastructure, supported by billions of dollars in financing from China’s policy and commercial banks. Guinea’s bauxite mines have been linked to serious environmental and social impacts, including improper land acquisition without adequate compensation or replacement land, pollution of water resources and destruction of local livelihoods. These impacts have caused frustration amongst the local population, leading to protests quelled with violence.

Although the bauxite from most of these projects is shipped to China for refining and converting into aluminum parts, much of it ultimately ends up in products such as cars produced by major international companies. Many of these companies have made supply chain human rights due diligence commitments and have signed on to stakeholder initiatives such as the Aluminium Sustainability Initiative. European car brands may soon have to comply with mandatory human rights due diligence laws, applicable to their supply chains. Chinese bauxite mines and aluminum good producers will need to be responsive to these requirements to maintain and increase their European customer base.

A similar story is playing out in Ghana, where Sinohydro and other Chinese companies plan to extract bauxite from under the sensitive and highly biodiverse Atewa Range Forest. This project has been subject to legal action by local NGOs, and in February 2021 three manufacturing companies – BMW Group, Tetra Pak and Schüco International – issued a statement expressing concern about the project and stated they would not source aluminium from it. As China continues to integrate into global supply chains, these issues will continue to arise, and will inevitably impact upon the way Chinese companies operate globally.

>> back to top

Policy Developments

White Paper on China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era

Guest article by Stella Hong Zhang, PhD candidate in Public Policy at George Mason University.

The publication of the White Paper on China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era (Chinese, English) in January 2021 was an exciting development for researchers of Chinese foreign aid. There are many reasons why this White Paper is significant. Starting from the terminology, China now officially adopts the term “international development cooperation” as a more “modern” concept to encapsulate its international development engagements, broadened from the old term of “foreign aid”. The adoption of this terminology is the result of China’s learning and reconceptualization from its own experience and international discussions.

Compared to previous White Papers on foreign aid, this document has a whole section that deals with the philosophical foundation for China’s international development cooperation. It refers to everything from the Maoist internationalism, to the values in the traditional Chinese culture, and links all these ideas to the “Global Community of Shared Future,” Xi’s signature slogan. Giving the document a stronger political flavor than previous iterations.

Aside from the rhetoric, this White Paper also provides a more structured explanation of the content of China’s international development cooperation. Previous documents contained very general statements about how China’s foreign aid promoted welfare and socio-economic development, but in this White Paper, two parallel sections elaborate specifically on how cooperation serves the BRI’s five pillars and the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, respectively. This suggests that China’s future planning will more consciously follow the frameworks from these domestic and international policy agendas where the two align.

The White Paper also contains some new theoretical grounding for economic development. With a dedicated section on the concept of “endogenous growth,” China is likely to strengthen its “capacity building” programs, which have traditionally taken the form of training for government officials and technocrats. China may increasingly engage in advising other countries’ development planning both as a form of “capacity building” and “policy coordination,” one of the pillars under the BRI.

You can read more of Stella’s analysis on this topic in Panda Paw Dragon Claw and listen to her discussing the White Paper on the China Power Podcast.

New Guidelines on Green Finance

President Xi’s announcement that China will go carbon neutral by 2060 has given renewed impetus to China’s state institutions to push forward new policies regarding climate finance. In February, Caixin reported that the People’s Bank of China is preparing a “package of policies” to support finance for green development. The bank is also working with the European Union on a common classification standard on green finance in order to promote cross-border investment, as well as taking steps to improve the financial system’s ability to manage climate change-related risks. Also in February, China’s State Council issued guiding opinions that seek to enhance China’s green bond market and support financial institutions to obtain green financing on international markets.

In an important development with relevance to overseas finance, China’s banking regulator issued trial Measures for the Management of Reputational Risks of Banking and Insurance Institutions. The measure calls on commercial banks to proactively manage reputational risk at all levels of bank activities down to the individual branch level and emphasizes social responsibility. This requires banks to set up or designate a dedicated department responsible for reputational risk management and to establish mechanisms to deal with complaints, reports, mediation and litigation. The measure also requires banks to establish information disclosure mechanisms, in order to avoid “misunderstandings” that may cause reputational risks. This applies to wholly Chinese banks, and joint ventures with other international banks. Importantly, it elevates reputational risks to a level similar to other categories, such as country and credit risk.

Importantly, under this measure the banking regulator is empowered to review banks against these requirements as part of its supervision process, and failures to comply can result in disciplinary action and may be factored into regulatory ratings, which can impact bank’s market access. For many years communities impacted by Chinese financed overseas projects and civil society groups working with them have struggled to engage with banks, and as such, this new trial measure represents a potentially important step forward.

>> back to top

Conclusion

Hard lessons have been learned overseas, with several Chinese projects suspended or renegotiated due to public discontent and host country concerns about unfavorable terms. High profile controversies around project’s social and environmental impacts have resulted in reputational harm, which China has been slow to respond to. At the same time, global and domestic economic conditions have led to a slowdown in China’s overseas investment. This period of cooling off potentially creates space for the further development of policies and guidelines by Chinese state institutions in the areas of green credit, and for a refocusing upon projects that contribute to, rather than conflict with, Chinese state commitments to ensure that the Belt and Road supports sustainable development via high quality projects. Although there is a long way to go, policy developments appear to be laying the groundwork for stronger mechanisms for dealing with these risks. Chinese policy documents are now referring to “high quality” projects and the recent white paper on overseas development cooperation explicitly discusses alignment with the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Given the current global economic situation, it is unlikely that we will see a major jump in China’s outbound investment and finance in the near future. Debt distress and the economic risks associated with it will likely dampen enthusiasm of both host countries and investors, meaning that the large number of mega infrastructure projects that characterized Chinese lending in 2015-16 will not be replicated any time soon. It is more likely that finance will flow to smaller projects, and projects facilitating industrial development, manufacturing and trade, which may deliver more immediate returns for hosts and investors. It is also likely that China’s commercial banks will continue to expand their global portfolios. However, one thing is clear: while the Belt and Road may be down, it is certainly not out.

Further reading

Johanna Malm (2020), ‘China-powered’ African Agency and its Limits: The Case of the DRC 2007–2019, South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA)

BRI International Green Development Coalition (2020), Green Development Guidance for BRI Projects Baseline Study Report.

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletters here.

If you haven’t already, you can also subscribe below to receive an email alert when our next newsletter is published.

This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of Oxfam Hong Kong.

(The contents do not necessarily reflect the position of Oxfam Hong Kong.)