China Global Newsletter | Edition 8: May 2023

Chinese Investment in Myanmar After the Coup

This past February marked two years since the Myanmar military overturned the democratically elected civilian Government and seized power. The country has since been mired in an increasingly dire political, economic and humanitarian crisis.

Despite the junta’s efforts to assert legitimacy and ease fiscal strain by keeping and attracting foreign investment, many high-profile international companies—facing reputational and myriad other risks—have announced plans to exit or pause operations. Other companies have remained in the country, but made an effort to publicly justify their decision to continue doing business with the junta. Chinese companies’ responses have been comparatively subdued—whether continuing operation as usual, as some have done, or withdrawing, they have for the most part made their decision quietly and without publicizing their reasoning.

As a major investor and Myanmar’s biggest trade partner, China’s willingness to do business with the junta could be crucial for the survival of the military regime. Many Chinese projects, given their large scale and proximity to conflict areas, already raised serious concerns before the coup. Under the current military regime, with violence and instability spread nationwide, concerns around the accountability and potential human and environmental impacts of these projects have only increased. This is especially true given that none of the projects have shown any signs of conducting adequate assessments for conflict-affected and high-risk circumstances to inform decision-making.

This edition of the China Global Newsletter assesses the status of high-profile Chinese investment projects (excluding contracting and aid projects such as those under the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism) in post-coup Myanmar, finding that most have struggled to move forward even with high-level political support from both sides. It examines the issues that have hindered Chinese projects, and how their potential environmental, social and human rights risks could be exacerbated in the current context. It also raises the possibility that this confluence of factors presents a potentially valuable opportunity for strengthening China’s regulations for doing business in conflict-affected and high-risk contexts, which could improve outcomes in Myanmar and elsewhere—wherever Chinese firms invest in these types of difficult environments.

Contents:

We want your feedback! Please take this brief survey to help us tailor future editions of the China Global Newsletter.

To Leave, or Not to Leave: The Business Dilemma in Post-coup Myanmar

Although the junta assured foreign investors that it had “largely restored national stability by the second half of 2021,” violence intensified throughout 2022. Pre-existing conflicts reignited and new anti-military armed groups became active in areas that were relatively peaceful before the coup. Failing to restore order amid widespread civil unrest and armed resistance, the military increasingly relied on the brutal “Four Cuts” strategy: indiscriminate deployment of airstrikes and artillery shelling, mass burnings of villages to displace civilian populations, and denial of humanitarian access. A recent airstrike on civilians in Pazigyi Village, Sagaing Region, is the most deadly example so far and resulted in over 160 deaths, including 35 children, according to the National Unity Government. With 255 out of the total 330 townships experiencing armed clashes between 1 February 2021 and 31 January 2023, nearly 3,000 people have been killed by the military, over 1.3 million displaced and more than 15.2 million face acute food insecurity, according to the United Nations. The Rohingya community, which has already endure prolonged misery, faces renewed intimidation and a dire future.

In the face of this turmoil, the junta extended the state of emergency for a second time in February 2023. This suggests that the planned election, which the junta desperately needs to legitimize its rule, will likely be delayed. Either way, the Secretary-General of the UN is concerned about the plan to hold elections amid “intensifying aerial bombardments and burning of civilian houses, along with ongoing arrests, intimidation and harassment of political leaders, civil society actors and journalists.”

With no sign of political stability on the horizon, the regime has also failed to stabilize the economy, exacerbated by its frequently changing rules and regulations. Business in the country is now facing increasing currency volatility, trade and foreign exchange restrictions, and regular power outages, on top of international sanctions and reputational risk. The junta has continued to see an exodus of major foreign companies, including the French energy giant TotalEnergies and the U.S. oil major Chevron, which until recently had endured years of criticism and lawsuits over their investment in Myanmar. Norway’s Telenor and Qatar’s Ooredoo in telecommunications, Australia’s biggest oil and gas producer Woodside, and ANZ bank are also among the many big names exiting the country.

Some companies, however, chose to stay or even fill gaps left by others. More shockingly, global investment funds carrying the environmental, social and governance (ESG) label held at least US$13.4 billion worth of shares in 33 companies found to have business links with the Myanmar military, according to an investigation by Inclusive Development International in 2022. Some of these firms are facing consequences. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund has divested from AviChina Industry & Technology and India’s Bharat Electronics for selling weapons to Myanmar. The Dow Jones Sustainability Indices removed the Indian company Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone due to “heightened risks to the company regarding their commercial relationship with Myanmar’s military,” although it kept Thailand’s PTT Exploration and Production Public Company (PTTEP), which took over the operation of TotalEnergies and Chevron gas projects following those companies’ exit.

Managing human rights risks doesn’t end with the decision to leave or not to leave. Many of the companies that pulled out continue to face heavy criticism for irresponsible exit, failing to conduct meaningful, if any, human rights due diligence to inform their decision and exit plan. For example, Telenor is facing a complaint from 474 Myanmar based civil society organizations to the Norwegian contact point for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, alleging it failed to properly assess the risks of the sale of its Myanmar operations, among other things.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Myanmar has plummeted since the democratic regime was toppled. Almost all newly approved FDI in the first year since the coup is from Asian countries, topped by China, according to the junta. Against this backdrop, the junta has described China as “the most important foreign investor.” Chinese investment could be crucial for the junta’s attempt to legitimize the illegal and unpopular regime, restore a veil of normalcy and “business as usual,” and refill the country’s foreign reserves.

Recommended Reading

An Evolving Framework for Outward Investment: A Chinese Approach to Conflict Sensitive Business

American Friends Service Committee published a Chinese think tank-NGO collaboration in which Jiang Heng assesses the risks that Chinese corporate actors face in investing in conflict-affected nations and proposes tools that Chinese actors might use to minimize these risks.

Heightened Human Rights Due Diligence for Business in Conflict-Affected Contexts: A Guide

United Nations Development Programme guidance for businesses and other actors on how to meet their responsibilities to carry out a heightened version of human rights due diligence in conflict-affected areas.

Behind the Smoke Screen: Chinese Investment in Myanmar Struggles to Move Forward

The Chinese government has often taken a pragmatic approach to political developments in Myanmar. China was the biggest investor in Myanmar when the previous military regime suffered international isolation between 1988 and 2010. With some major Chinese projects facing strong headwinds following the political reforms that began in 2011, including the suspension of the Myitsone dam due to massive public opposition, China eased into nurturing a relationship with the National League for Democracy (NLD), the opposition party at the time. This paid off, as the party won a resounding election victory in 2015.

Several important agreements were signed, especially around the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), which is a crucial part of the Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar and aims to inject new momentum to a cluster of long-existing plans for infrastructure projects linking the two countries. During Xi Jinping’s trip to Myanmar in 2020, 33 MoUs were signed, which included a number of major infrastructure projects. Learning from the lack of scrutiny of Chinese projects under the previous military regime, the civilian government tried to increase checks and balances. It renegotiated the Kyauk Phyu Special Economic Zone Project which was agreed under the previous regime and successfully persuaded China to agree to allowing international tenders and finance for the CMEC projects.

Since the coup, the junta has regularly boasted of the progress made on high-profile Chinese projects. This is often interpreted as Chinese companies, backed by Beijing, supporting the military regime or even seizing the opportunity to advance their projects in Myanmar. This narrative has served the junta well, reinforcing their claim that the regime has weathered international sanctions.

However, a closer examination paints a mixed picture. While projects with long-term strategic value for China have resumed preparatory or planning work, and some new and smaller projects have been proposed (seemingly to test new ground), there has overall been limited movement on investment projects that were not already underway. Interestingly, several major projects that were gaining momentum before the coup have stalled, despite being publicly boosted by the junta, suggesting that the Chinese government and investors are cautious about surging risks in post-coup Myanmar. Despite the limited progress since the coup, China’s plans for increasing connectivity and economic cooperation with Myanmar over the long term remain unshaken, suggesting many projects might proceed once the situation is deemed suitable.

Beijing and the junta resumed talks about economic cooperation in 2022, agreeing to work on the following priorities: China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, cross-border power grids and connectivity, industrial parks, and ensuring the smooth operation of China-Myanmar oil and gas pipelines. However, an examination of the status of the key investment projects under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor and agreements signed during President Xi’s visit in 2020, as well as key energy projects, shows that most projects still face headwinds (see details on the status of these projects here).

China’s latest FDI data, which tracks actual investment made (not simply approved), shows a mere 18 million USD making its way to Myanmar in 2021, almost a 93 percent drop compared to 2020, the year of the COVID outbreak. The pandemic likely affected project activities on the ground, but the concerns over risks arising from the coup have also reined in progress. Chinese government progress updates in 2022 reveal that some projects, such as the three Cross-Border Economic Cooperation Zones and the Myitkyina Economic Zone stalled due to the pandemic and the political situation. Beijing also indicated that transportation connectivity projects such as the Mandalay-Tigyaing-Muse Expressway and Kyaukphyu-Naypyitaw Highway would depend on the political situation. Nonetheless, these projects remain in the government plans and local governments in China have been active in paving the way for work to be resumed when the situation allows.

For the most strategic projects, China appears to be willing to play the long game, with Chinese stakeholders patiently pushing forward incrementally. The Kyauk Phyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and Deep Sea Port project and the China-Myanmar railway promise China access to the Indian Ocean, and are seen as two of the most strategic Chinese projects in Myanmar. Both projects have resumed preparatory work that is low-cost and non-committal. The Kyauk Phyu project announced the tender result for field surveys in late 2021 after 8 months of silence, and for the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) consultant in 2022. They are now being implemented. The EIA was also quietly finished and was reportedly approved for the Muse-Mandalay section of the China-Myanmar Railway. The feasibility study for the Mandalay-Kyauk Phyu section has not yet been conducted, although China and the NLD government agreed not long before the coup to finish it within eighteen months. As conflict continues to rage, implementing these projects will be challenging.

Groundwork has for the most part been observed in projects that had already started construction before the coup, such as the Kyauk Phyu Gas Power Station by a PowerChina joint venture. One exception is a group of five small solar projects (160 MW in total) also invested in by PowerChina. China also celebrated trial testing of a new trade route tagged the “China-Myanmar New Passage” (also “China-Myanmar-Indian Ocean New Channel” or a part of the “New International Land-Sea Trade Corridor”) enabled by a new section of railway in China that connects to already existing roads in Myanmar to boost future overland trade. Some Chinese media reports led to misunderstanding that China had completed a new railway in Myanmar. A junta official confirmed that it was not true and even complained about China “spreading propaganda.”

For projects that are relatively less strategic, the uncertain prospects seem to have deterred investors. Soon after the coup, military chief Min Aung Hlaing twice pledged to push forward the Hatgyi dam along the Salween River. The project has long been seen as motivated by military considerations, and has stalled for years since it triggered clashes between the Myanmar military and the Karen National Union (KNU) in 2014. Two years on from his 2021 pledge, there has not been any administrative progress or movement on the ground. Nor have there been any responses by the major developer—China’s hydro giant Sinohydro (now a part of PowerChina) or other joint developers. As armed conflicts intensify in the project area, it is difficult to imagine any sensible investor, even motivated by strategic interests, would see the junta’s enthusiasm for the project as an opportunity.

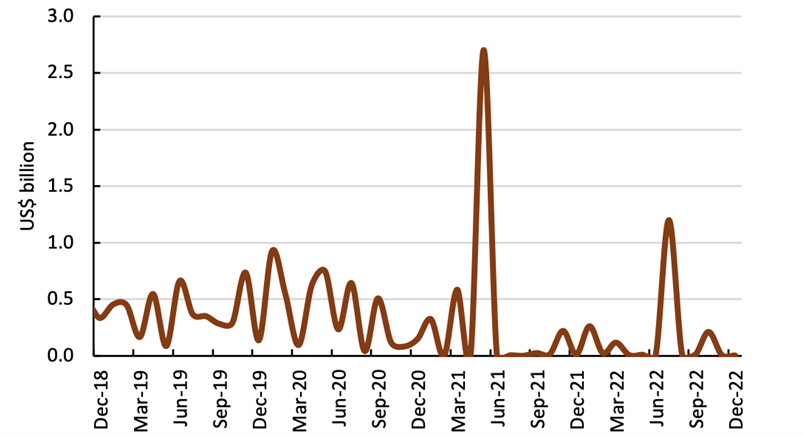

Another project the junta has publicly boosted is the 1,390 MW Mee Lin Gyaing Integrated Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) to Power Project, to be developed mainly by a provincial state-owned enterprise of China. Already at an advanced stage of the permitting process, the project was awaiting official approval at the time of the coup. In May 2021, the military regime announced approval of 15 projects, including Mee Lin Gyaing. Priced at US$2.5 billion, the approval of the project boosted the otherwise negligible FDI commitments that year (see chart below). However, no progress has been reported since then, and a year later the junta proposed to package it as a CMEC project, in the hope of gathering support from the China side to move it forward.

Approved FDI in Myanmar

Source: World Bank, January 2023: Myanmar Economic Monitor

The financial loss suffered by other companies operating in the energy sector may explain the wait-and-see approach. One of these companies is VPower, whose major investor is the Chinese state-owned conglomerate CITIC Group. The company’s Myanmar portfolio went from being its greatest prospect to its greatest liability. Six days before the coup, the company posted a positive profit alert, forecasting that its new LNG plants would bring a 70 percent profit growth in 2020. However, within the first half of 2022, the joint venture’s operation in Myanmar incurred a loss of 6.8 million HKD. A joint venture between VPower Group and a Chinese state-owned firm had to suspend two LNG power plants, despite Myanmar’s worsening power shortage. Operational challenges and foreign exchange losses were cited as the main reasons. VPower also decided not to renew two other power projects citing “the occurrence of political events and social unrest.”

Also in the energy sector, Chinese state-owned and private companies won 28 out of 29 solar tenders called by the civilian government in 2020, offering power purchase prices much lower than their competitors. After the coup, however, they repeatedly postponed signing the power purchase agreements at the original bid prices and implementing the projects. As a result, the junta reportedly cancelled 26 of the projects and proposed blacklisting non-compliant companies. Sungrow, China’s largest photovoltaic inverter manufacturer and the main winner of the tenders, disclosed that they have taken a 90 million RMB write-off due to the cancellation. Subsequently, the military regime called for another two rounds of solar tenders. Only two Chinese companies made bids.

The wide range of risks created or exacerbated by the coup will continue to be a major impediment to Chinese companies investing in Myanmar. Although there are frequent greenlights from the junta, Chinese firms still need to balance the books and navigate the soaring risks of project financing and operation, especially considering that many of the major projects are located in conflict-affected areas. Even with a significant dose of pragmatism, post-coup Myanmar is now an extremely risky place to invest, especially in comparison to other emerging markets.

Chinese Projects Under Fire

The crucial factor that has held back or slowed down Chinese projects in Myanmar is the security situation. Several major Chinese projects in operation have come under fire since the coup, although China has reportedly urged both the junta and the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) to safeguard its investments. In recent years, Chinese firms have been targeted by armed groups in several global conflict areas, most recently in the Central African Republic where nine Chinese nationals were killed at a gold mine in March. The risk to employees (both Chinese and local) and assets is very real, as is the risk that the presence of Chinese projects could further exacerbate conflict.

The Letpadaung copper mine, praised by some Chinese state media as an “iconic demonstration” of the BRI, has been severely hit by post-coup conflicts. So were the two other mines also run by Wanbao Mining, a subsidiary of an arm of China’s state-owned defence company China North Industries Corporation (NORINCO). Located in a hotbed of clashes in Sagaing Region, where the military recently dropped bombs and fired on a crowd of civilians, the violence at and around the mines significantly intensified following a rumor in April 2022 that the operation would resume after a long halt in production after workers went on strike soon after the coup. Subsequently, 16 resistance groups issued a joint statement threatening to attack the mine. This was followed by an ongoing cycle of violence escalation, with the Myanmar military deploying more troops and raiding nearby villages, pledging to guard the mines and their output supply chains, which triggered further resistance attacks. With production paralyzed by strikes and conflicts, Wanbao has been relying on its copper inventories to continue exports to China.

Having long been a source of public fury before the coup due to land disputes and severe environmental impacts, the three mining projects have become key targets of anti-regime forces for multiple reasons. First, the projects are jointly owned by Myanma Economic Holdings Ltd. (UMEHL), a military conglomerate, and have been an important source of revenue and foreign currency for the military, which in turn funds the war against the Myanmar people. It is estimated that the three mines together contributed US$604 million to the junta’s coffer in the 2020-21 fiscal year. Second, the site of the Letpaduang mine has allegedly been used as a base by the military. Third, the military have committed alleged atrocities to deter resistance groups, such as torching villages and torturing and dismembering civilians including two local employees of one of the mines.

For similar reasons, the power supply to Myanmar’s biggest nickel project was blown up in January 2022, bringing production to a halt. Run by China Nonferrous Metal Mining (CNMC) and the state-owned No.1 Mining Enterprise of Myanmar, the mine is believed to have supplied US$121 million to the junta in in the 2020-21 fiscal year. Although its infrastructure has not been targeted directly, the China-Myanmar Oil and Gas Pipelines have been caught in crossfire between resistance groups and the military, in one case resulting in the death of three police officers guarding the facilities. Long before the coup, Chinese government think tank researchers had already raised security concerns regarding the project, given the protracted armed conflicts in Myanmar and the lack of conflict analysis conducted in the preparation and development of the project.

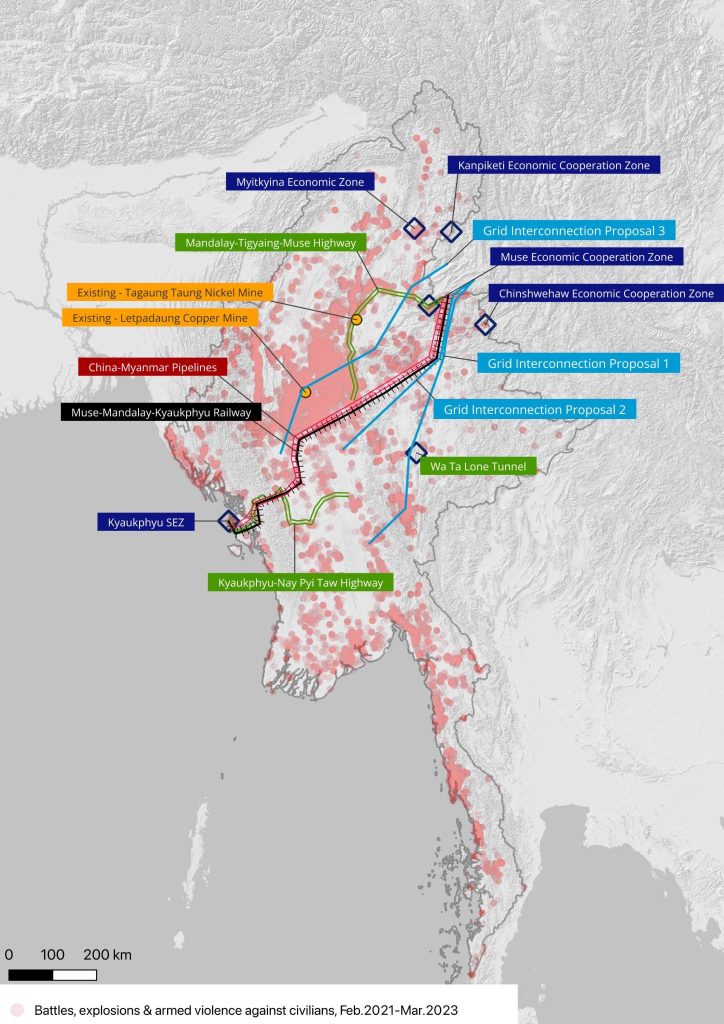

Overlaying major Chinese infrastructure, industrial and resource projects with conflict hotspots in Myanmar, it is clear that both operational and planned projects face heightened conflict risks. The Institute for Strategy and Policy estimated that at least 300 clashes took place in the townships hosting China’s major projects between February 1, 2021 and October 31, 2022, with the number in 2022 doubling the previous year. As can be seen in the map below, the pipelines are in a major conflict hotspot, as is a key route of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which includes several important projects such as the China-Myanmar railway.

Key Chinese Investment Projects in Myanmar

Map by Inclusive Development International, conflict data from Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

Although the parallel National Unity Government (NUG) confirmed that they did not have a “policy to attack the investments of neighboring countries,” some resistance groups have claimed that they are ready to attack what they see as “junta projects,” with one People’s Defence Force officer saying in 2023 that they are “not worried about upsetting the Chinese.” Chinese companies will have to reckon with these risks, but also be aware that simply bolstering security has a high likelihood of further inflaming tensions, especially if those deployed to guard projects continue to commit atrocities against civilians, further contributing to cycles of violence.

Threats do not only come from direct fire. The government of Baoshan, Yunnan Province, has pointed out the significant security risk to Chinese projects in Kachin, noting that it has been difficult to walk the fine line between the Myanmar military (and the militia alighted with it) and various local ethnic armed groups.

Putting Oil on the Fire: Heightened Social, Environmental and Human Rights Risks

Within this extremely volatile context, the social, environmental and human rights risks of the major Chinese projects in Myanmar call for urgent reexamination, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

Myanmar has a long history of foreign investment and development projects exacerbating abuses and fueling conflicts. Infrastructure projects such as roads and railways can be particularly sensitive, since the Myanmar military often uses—or is at least perceived as using—them to expand state control in conflict-affected areas. Yanghee Lee, the former Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, stated in her report in 2014 that she was “struck” by the information received regarding the impacts of large-scale development projects, particularly on vulnerable groups. Among the documented allegations, the issue of land confiscation and forced eviction stands out in conflict-affected areas, where the widespread customary land use rights of many ethnic groups are not protected by national policies and where restitution rights of returning refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) are not secured. Other widely documented violations include forced labor, violence committed by public and private security forces in relation to project operation, harassment and intimidation by state agents, arbitrary detention and torture.

Although China presents CMEC projects as a path to peace and stability, Chinese projects in Myanmar and elsewhere have long been criticized for their lack of conflict sensitivity, which has been acknowledged by a researcher at a think tank under the Ministry of Commerce of China. In this regard, statements by Wanbao Mining in response to threats to and attacks on the mines are revealing. Instead of addressing the key concerns over their business relationship with the military and the military’s heavy presence and atrocities conducted around the project, statements emphasized their health, education and welfare programmes and donations. Previously, the company’s community engagement was already criticized for being insincere, seen as an easy fix to brush off outstanding grievances related to land acquisition and resettlement.

To adhere to the UNGPs, responsible businesses should conduct human rights due diligence (HRDD) throughout the project cycle. The norm of undertaking heightened HRDD in conflict-affected and high-risk circumstances has also been established, and is echoed by the Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Mineral Supply Chains, issued by the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters (CCCMC). However, no major Chinese projects, planned or operating in Myanmar, have shown any signs of conducting HRDD to inform decision-making by meaningfully consulting with affected rights holders, local human rights defenders and experts. In fact, one can hardly find any trace of the coup or ongoing conflict in the company communications about the projects as they press ahead.

For projects that are still planned or are in their early stages, these issues are even more pertinent, as this is a crucial time to properly assess risks and potential impacts to inform sound project decisions. Both the Kyauk Phyu SEZ and the China-Myanmar railway have conducted EIAs, as is required by Myanmar law. However, the part of the EIA report of the China-Myanmar railway disclosed in July 2022 makes no mention of armed conflicts or the coup, only communal conflicts between ethnic groups. Public consultations with affected communities for this EIA were conducted in 2019, which are unlikely to reflect current public opinion given the dramatic change in the situation. Rushing through the process while ignoring the context of conflicts paves the way for rights violations and future violence. Even before the coup, people displaced by conflicts in some of the areas along the planned railway route, who could not attend the EIA consultation, voiced concerns that their homes and farmlands will be seized in their absence. What’s more worrying, local environmentalists have pointed out that the EIA process lacked transparency and adequate consultations. Whether people can safely voice concerns is another open question, given the experience of intimidation and threats during the construction of the China-Myanmar pipeline under the previous military regime.

Recruiting qualified international consultants is also a challenge, as most now stay clear of Myanmar over reputational or security concerns. Although the Kyauk Phyu SEZ called for international tenders for the EIA in January 2021, this was cancelled as “the number of bidders were less than desirable to continue with a competitive process.” Instead of taking this as a warning sign, the developer simultaneously announced a new “selected tender process” for consultants, without explaining how this process could ensure the quality of the consultant under such circumstances. In the end, the consultant selected was a Myanmar company, mainly known for marketing research and surveys, with an unknown track record of conducting EIAs for projects at such a scale.

China’s dependence on the junta to perform state functions, such as providing security and acquiring land for projects, adds oil to fire. After the coup, Chinese companies and government actors repeatedly called for protection from Myanmar’s public security forces in response to threats to projects, which has led to increased tension and a worsening human rights situation in most cases. Deployment of more troops to the project area of the Letpadaung mine caused thousands of villagers to flee their homes. The Myanmar military has laid land mines to secure the China-Myanmar pipelines, risking surrounding residents’ lives and denying them the access to source food from these areas. In this context, it is hard to see how the junta will conduct land acquisition appropriately for the large-scale Chinese infrastructure projects in a manner that respects human rights. A major lesson learned from the Myanmar–China Oil and Gas Pipelines is how alleged poor management of land acquisition and compensation by the authorities under the previous military regime, with a process marred by corruption and extortion, became the central cause of public protests.

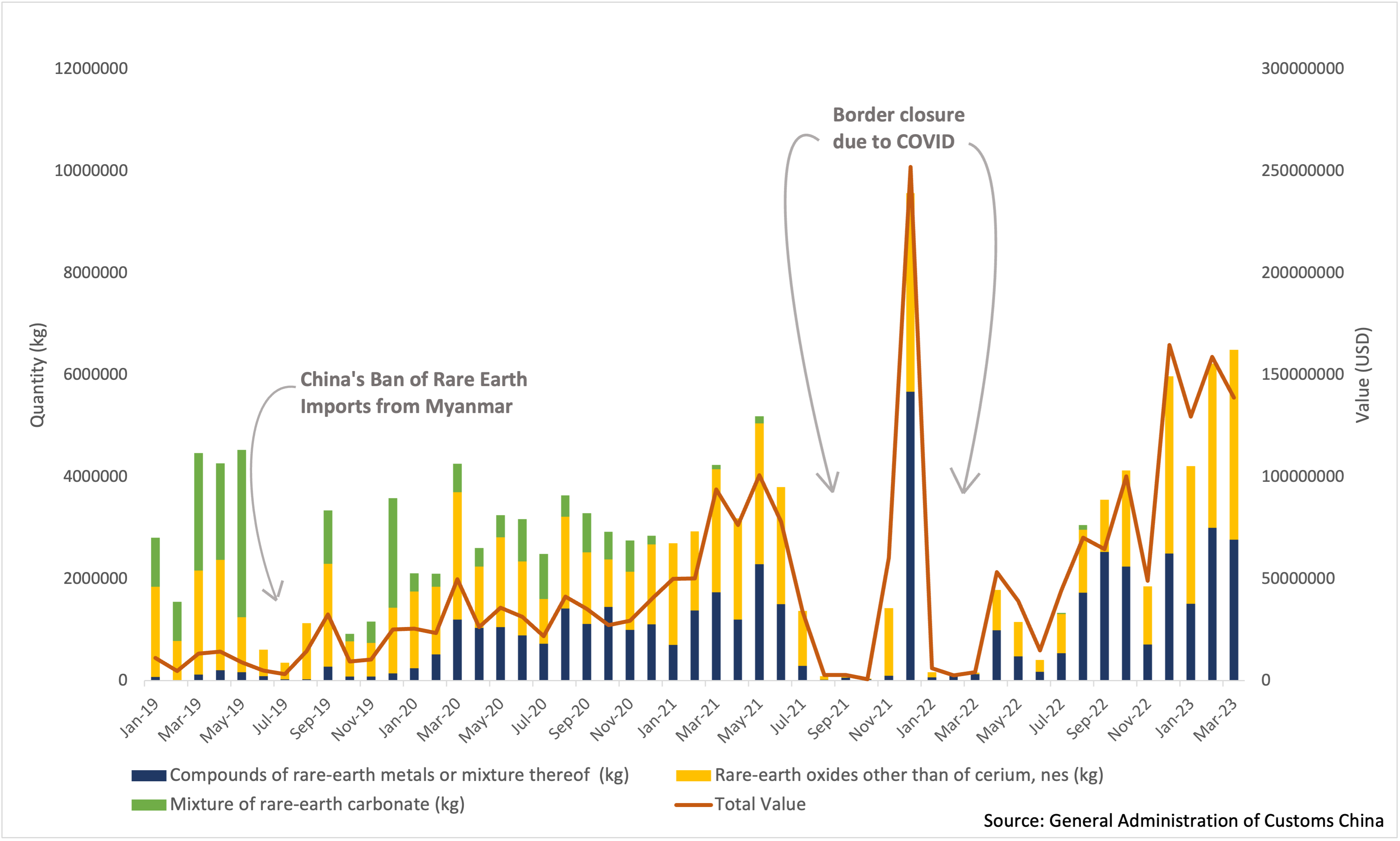

China’s strategic supply chains are also exposed to risks stemming from a vacuum of accountability. This is illustrated well in the case of Myanmar’s heavy rare earths mining industry, which exports entirely to China. Since the coup, there is an overall increase of China’s imports of rare earths from Myanmar, regardless of the interruptions caused by COVID, as illustrated by the chart below. Most of the mining is illegal and concentrated in areas controlled by armed groups under or aligned with the Myanmar military, but some mines are controlled by local ethnic armed groups. Having long been a severe threat to the local environment and a governance problem, illegal rare earths mining has expanded since the coup, with even less supervision than before. Since September 2022, local communities have been protesting against rare-earth mining allowed by a major ethnic armed group in areas bordering China, which led to the group’s recent decision to halt mining. It has been reported that these mines were backed by Chinese investment and rare-earths illegally mined in Myanmar have supplied Chinese state-owned processors, who in turn provide indispensable inputs for global renewable energy and transition industries. Yet there have been no signs of these companies conducting supply chain due diligence as the CCCMC guidelines mentioned above advocate.

China’s Rare Earth Imports from Myanmar (January 2019 – March 2023)

Conclusion

In the late 2010s, Chinese officials and policy documents began to stress the need for “high quality” and “sustainable” overseas projects. However, the approach adopted in major Chinese projects in Myanmar casts doubt on this commitment. The practices of many developers contrast starkly with the official goal of establishing a “new model of international relations based on mutual respect, equity, justice and win-win cooperation” and the building of “an open, inclusive, clean and beautiful world that enjoys lasting peace, universal security and common prosperity,” as articulated in the State Council’s 2019 white paper China and the World in the New Era. This discrepancy threatens to further fuel the widespread cynicism among the Burmese population about Chinese investment.

While China has strengthened policies and guidelines related to the social and environmental responsibilities of Chinese overseas projects, implementing frameworks are still lacking, and there is a significant gap regarding conflict-sensitive investment. To date, non-binding guidelines issued by the mining industry association CCCMC, mentioned above, are the only document providing guidance on doing business in conflict-affected areas. China’s policies impose stricter standards for approval of investment in “sensitive countries and regions,” including those experiencing war or civil disturbance, and instruct state institutions to “guide companies to invest in a prudent manner, and give the necessary guidance and reminders based on the specific situation,” but the meaning of “prudent manner” is not defined, nor are there any clear requirements for heightened due diligence in conflict-affected areas.

The issues raised here demonstrate the extreme risk associated with major projects moving forward in post-coup Myanmar. These risks will have repercussions for Chinese enterprises and their financiers, with the chance of delays, protest and violence likely to slow projects and increase costs. They will come with reputational and political risks for the Chinese state, which is seen by many as propping up, whether intentionally or not, a brutal and unpopular regime in Myanmar. Most importantly, the weight of unaddressed conflict, environmental and social impacts will be borne most heavily by the Myanmar people. With the current situation showing no sign of abating, this presents a potentially valuable opportunity to strengthen China’s regulations for doing business in conflict-affected and high-risk contexts. With Chinese firms active in numerous global conflict zones, this could have positive ripple-effects on a wider scale, wherever Chinese firms invest in these types of difficult environments.

Further reading

Findings of a six-month investigation by Global Witness follows the outsourcing of the highly toxic heavy earth industry across the Chinese border into Myanmar.

Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Mineral Supply Chain

The China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters (CCCMC) was the first Chinese industry association to issue guidelines setting out frameworks for assessing and managing conflict risks in mineral supply chains.

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletters here.

If you haven’t already, you can also subscribe below to receive an email alert when our next newsletter is published.

This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of Oxfam Hong Kong.

The contents do not necessarily reflect the position of Oxfam Hong Kong.