China Global Newsletter | Edition 9: July 2024

Improving Accountability at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

Almost 10 years into its existence, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has over 100 member states and has financed more than 270 projects in close to 40 countries. Over the years, the bank has developed policies and procedures for managing social and environmental risk in the projects it finances, and for ensuring accountability when harm occurs, but these are still evolving and need improvement.

In 2019 the bank established an accountability mechanism to receive and address complaints from people who believe they have been negatively impacted by AIIB projects, yet it has only rarely been used and in five years, not a single complaint has been deemed eligible. Civil society groups have called attention to key weaknesses preventing the mechanism from serving its purpose, and the bank is currently in the process of reviewing the policy that governs it.

- The AIIB at ten years

- Developing a framework for project risk management and accountability for harm

- Reviewing the Project-Affected People’s Mechanism

- Removing roadblocks to accountability

- Looking to the future

The AIIB at Ten Years

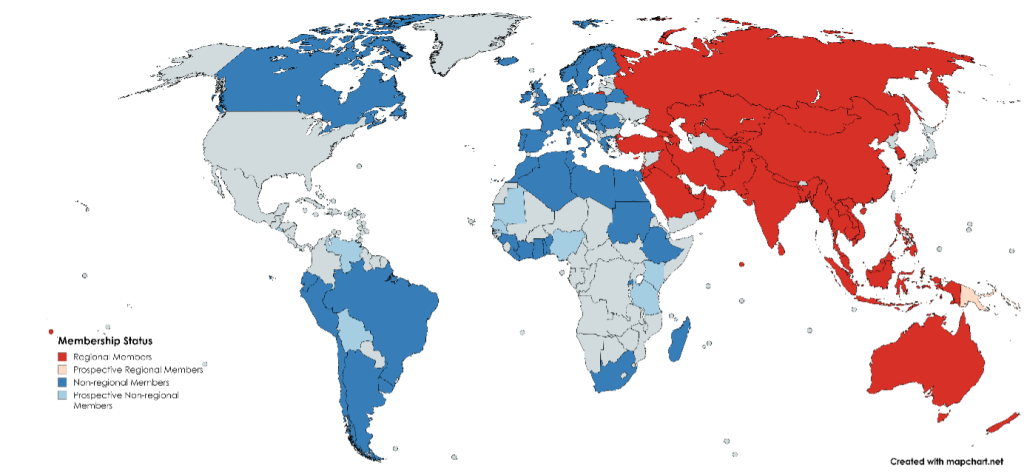

Since approving its first project in June 2016, the bank has built a portfolio of 272 projects worth over US$53.5 billion as of July 2024. Its membership has grown from the 57 founding members to over 100 countries, expanding beyond Asia to include most of Europe, Australia, Canada, and an increasing number of nations from Latin America and Africa.

AIIB Members as of July 2024

China has a voting share of over 26.5%, meaning it has a powerful voice in bank decision making. The second biggest shareholder is India, with a much smaller 7.6% share of votes. Shareholders are organised into constituencies, which means voting shares can be pooled. For example, the two European constituencies have a combined vote share of around 22% if they vote as a block. Notably, the U.S. and Japan, which are top shareholders of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, are absent from the AIIB’s membership.

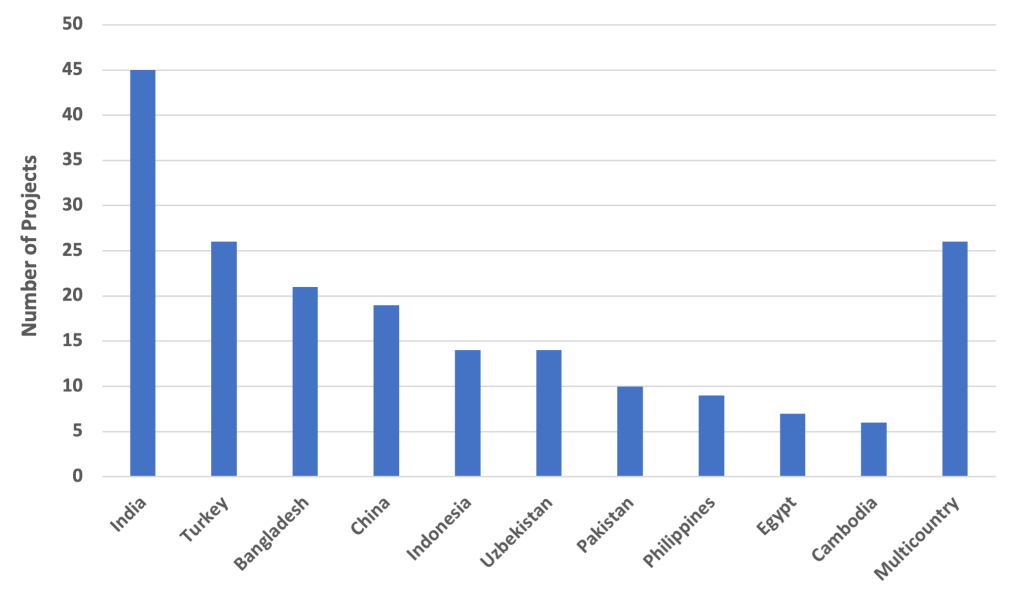

The bank has projects in 38 countries, but the top three recipients—India, Turkey and Bangladesh—account for more than a third of all approved projects. India is by far the top recipient of AIIB loans, accounting for almost 20% of the bank’s projects.

Geography of AIIB Projects (top 10 destinations)

Energy projects are the top recipient of AIIB financing, followed by transport. The two sectors combined account for almost 40% of projects. Beyond the traditional transport and energy infrastructure projects, the AIIB has been expanding its focus into digital, health and other social infrastructure. In addition to direct project financing, the AIIB has rapidly expanded its indirect financing through banks, funds and investment portfolios over the past two years, which now account for more than a quarter of its projects.

Developing a framework for project risk management and accountability for harm

While the AIIB’s core business of financing infrastructure is badly needed across Asia and beyond,. And in many countries, people who raise concerns or objections to such projects face reprisals. Managing these risks is key to preventing harm and ensuring AIIB projects actually provide the benefits intended.

Since the 1980s, development banks have required governments and companies to agree to environmental and social standards in order to secure financing. While they are not perfect, when applied properly, these standards help mitigate the harm that infrastructure projects can cause, and provide platforms for recourse for those who are impacted.

In 2015, a few months before becoming operational, the AIIB began to develop its Environmental and Social Framework Following a contentious initial drafting process, the framework was adopted in 2016.

After the adoption of the Environmental and Social Framework, the bank began work on developing its accountability mechanism for holding the bank to those promises. The Project-affected People’s Mechanism (PPM) came online in March 2019. The mechanism receives submissions from people who believe they have been or are likely to be adversely affected by AIIB’s failure to implement its Environmental and Social Policy.

The mechanism can address the complaints from project-affected people through three different functions: (1) Project Processing Queries, in which the PPM facilitates rapid resolution of simple and straightforward matters that are raised before the AIIB approves a project; (2) Dispute Resolution, in which the PPM facilitates a dialogue between the AIIB, project-affected people and/or bank clients with an aim to reach mutually agreeable solutions to the problems raised; or (3) Compliance Review, in which the PPM investigates whether the AIIB has complied with its obligations under its Environmental and Social Framework.

Reviewing the Project-Affected People’s Mechanism

Despite 272 projects having been approved at the time of writing, the PPM has received only three submissions and has not yet accepted a single complaint. Given the nature of the projects the AIIB funds, and experiences at other development banks, it is extremely unlikely that the portfolio is free from projects that have caused negative impacts. Civil society groups, including Inclusive Development international, have identified various potential reasons for this gap (returned to below). The bank is now in the process of reviewing the mechanism (when the bank adopted the current policy on the PPM, it included a built-in review after five years, which has come due).

Further Reading

Project-affected People’s Mechanism website.

AIIB (2024)

The consultation process is now ongoing and—is much more extensive than those conducted for past AIIB policies and strategies, with the bank publishing a roadmap in December 2023 and a more detailed approach paper in early 2024.

In-person and virtual consultations began earlier this year and are ongoing, and the bank is accepting submissions until the end of July on the existing PPM policy. This will feed into the review process, and a second phase of consultations will be opened where the public will be able to comment on a draft of the revised policy in late 2024 to early 2025.

If you wish to get involved in this process, full details can be found here.

Since the AIIB was established, it promised to be a “lean” institution, but at the same time committed to meeting the standards of its peer institutions. Previous policy consultations at the AIIB , and the consultation in 2015 on the bank’s original Environmental and Social Framework was grossly inadequate. However, since then several important civil society recommendations on the PPM review process were taken up by the bank and a review of the updated process by Accountability Counsel found it to be more comprehensive than that of the Asian Development Bank, which is also in the process of reviewing its accountability mechanism this year.

Open, inclusive, and transparent consultation on key bank policies is crucial to ensure accountability but also results in stronger policies. If the voices of affected people and civil society are not heard, policies will be less responsive and mechanisms less accessible.

Removing Roadblocks to Accountability

The bank’s PPM review process has included an important feature that has not been part of previous policy reviews: the bank commissioned an external review, which was published in June.

The external reviewer engaged with a range of stakeholders, including civil society organizations and experts in the field of environmental and social accountability.

Last year, Inclusive Development International worked with a group of global partners to assess key barriers that may be contributing to the limited number of complaints received by the PPM. In Roadblocks to Accountability, we identified gaps and shortcomings in existing bank policy that we hope to see addressed in the coming review, highlighting issues around complaint eligibility, disclosure, project-level grievance redress mechanisms, and overall accessibility.

The principal roadblock to accessing the PPM is the eligibility criteria set out in existing bank policies. As of 2023, 38% of projects in the bank’s portfolio were ineligible to access the mechanism. The majority of these cases involved projects co-financed with other banks. Bank policy states that where the AIIB has an agreement with a partner institution to do so, complaints from project-affected people must be submitted to the lead financier, which is generally not the AIIB. This limitation is unique to the AIIB and renders a large portion of projects that it finances ineligible for the PPM

In our 2023 assessment of the bank’s portfolio, we found the majority of projects that were eligible for the PPM were financial intermediary projects. These involve the bank lending money to or investing in another institution which then goes on to provide loans to or invest in “subprojects.” Financial intermediaries are required to have in place policies that ensure subprojects are implemented in a way that is in line with the standards of the AIIB. However, following the flow of funds from the AIIB to these sub-projects can be difficult, which means that communities affected by the subprojects likely do not know that the AIIB is involved or that they have the option of submitting a complaint to the PPM.

Adequate disclosure is crucial to ensure that the public actually knows that the AIIB is involved in a project. However, we found gaps in the disclosure of both the bank and intermediaries. In some cases, it is challenging to identify intermediary project portfolios, and where they are disclosed, project information is often minimal. Furthermore, in a third of projects we identified, the intermediary had not disclosed the existence of the PPM and of project-affected people’s right to file submissions to it, despite this being required under AIIB policies.

It is important to acknowledge that although the bank is now approaching a decade of operations, it is still not especially well known to the public in the countries where it is financing projects. In contrast to institutions like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, the AIIB has no country offices, and this lack of physical presence, and its relatively small portfolio in most countries, contribute to the lack of public awareness about the bank and its activities. This makes high standards for project disclosure even more crucial, and increases the need for the PPM to enhance public outreach.

Civil society groups have raised objections to a variety of other accessibility barriers that unnecessarily restrict project-affected people from using the PPM to address harm. For example, the existing PPM policy does not allow complainants to select international organisations to represent them when filing a complaint, unless they can demonstrate that in-country representation is unavailable.

Another problematic barrier in the current policy is the requirement that people first make “good faith” efforts to resolve concerns at the project level and with bank management before a complaint can be eligible to the PPM. There can be good reasons why affected people may not feel safe raising their concerns at the local level, and the PPM is the only accountability mechanism that has this double-layered requirement.

For a more detailed review of the existing barriers to accountability and civil society recommendations on how they should be addressed, you can read Roadblocks to Accountability here in full.

Further reading

Recourse, Accountability Counsel & Inclusive Development International (2024), Roadblocks to Accountability: Addressing the accessibility crisis in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s review of its Project-affected People’s Mechanism.

Radhika Goyal (2024), External Review Report Recommends Sweeping Changes to the AIIB’s Independent Accountability Mechanism, Accountability Counsel.

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletters here.